Blue cheese with sage and french bread - Oil on canvas board 8" X 6"

Lemons on wood box - Oil on canvas board 8" X 6"

Lemons and green depression glass plate - Oil on canvas board 8" X 6"

Lavender tied with a blue bow - Oil on canvas board 8" X 6"

Lemons with Pink lemonade in blue spotted depression glass - Oil on canvas board 8" X 6"

Lemons with Pink lemonade in blue spotted depression glass - Oil on canvas board 8" X 6"

Fresh pomegratate by Buddhist stupa offering bowl - Oil on canvas board 8" X 6"

Collection of Brent White

Fresh papaya by Buddhist stupa offering bowl - Oil on canvas board 8" X 6"

Collection of Brent White

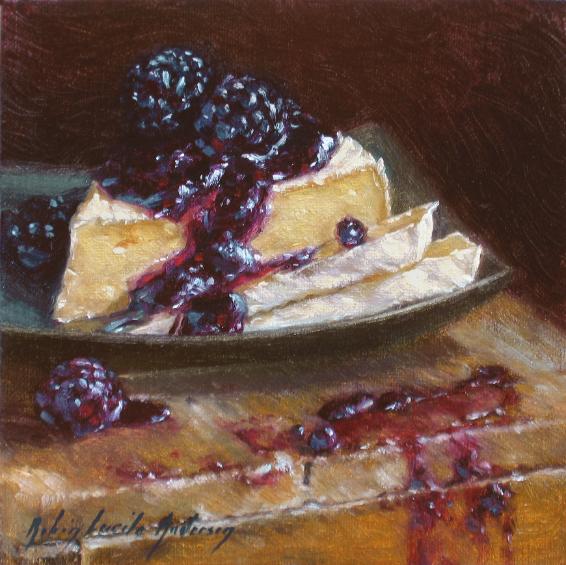

Brie cheese and blackberries - Oil on canvas board 6" X 6"

Brie cheese and berries - Oil on canvas board 6" X 6"

Collection of Brent White

Cranberries on plate on red and white stripes - Oil on canvas board 8" X 6"

Geraniums in jam jar - Oil on canvas board 10" X 8"

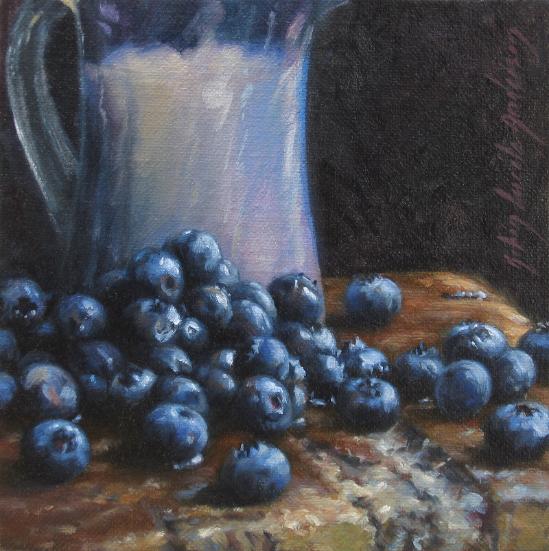

Blueberries with cream in blue glass pitcher - Oil on canvas board 6" X 6"

Blueberries with cream in blue glass pitcher - Oil on canvas board 6" X 6"

Pink, white and yellow roses in glass vase - Oil on canvas board 6" X 6"

Roses in swirly glass vase - Oil on canvas board 6" X 6"

Two lemons in front of blue tile - Oil on canvas board 6" X 6"